Always be prepared

April 8, 2025

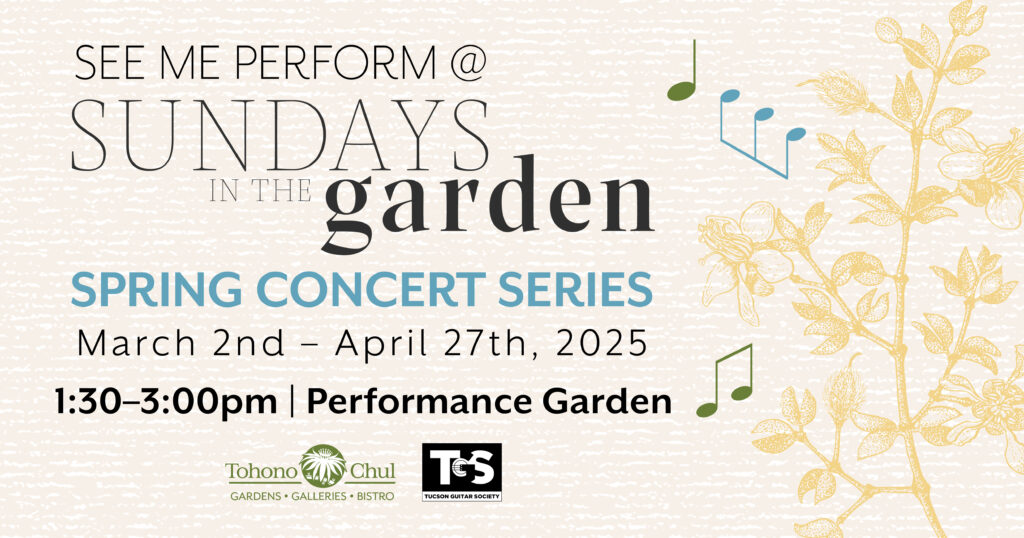

It is nearing the end of this project, and if you can believe it, developments are still happening to this day; I guess that’s just the art world. One week closer to the big goal of this project, the Tohono Chul performance on April 20th, one week closer to the end of the semester, and that means one week closer to graduation! A lot is happening these days, and I’m fine saying that it really is hard to juggle it all.

If you haven’t been following along with this aforementioned project, I hope that after reading this you’ll want to know more and you might read a previous post or two, but you’re in luck… because it’s changed!

I know, one week until the culmination of this whole thing and it’s changing, how is that possible. Well…

Being flexible

My initial goal this semester was to help jumpstart my duo project with my violist partner Katie Baird. We both love music in non-traditional performance spaces, including outdoors, but especially in medical environments. We have both, respectively, performed more than 100 hours in healthcare facilities, and with Katie’s background in performing for assisted living facilities, our goal was to perfect some repertoire for our viola and guitar duo and perform it in small concerts for residents of assisted living communities. To top it all off, as a part of the Tucson Guitar Society’s Sundays in the Garden concert series, a series I organize, we were set to perform that same music in a duo concert, spreading the word about the work we are passionate about to build awareness of its importance.

Nothing is life is set in stone and things are always changing. Unfortunately, this project will not end in the way that we hoped, with the biggest development coming this week with a change of plans.

On April 20th, Easter Sunday, I will be performing a solo concert at Tohono Chul, instead.

As much as we wanted our duo to flourish, this probably is not the right time. Again, nothing in life is permanent, so who knows what will happen in the future, but for now, we’ve had to regroup.

With a concert only two weeks away and a complete change of plans, it’s understandably been a stressful time, but it’s managing that stress that I’ve learned to be a bit better at in this process, which was not easy.

Struggling to manage stress

So, I wasn’t completely left in the lurch with this change; I’ve been preparing for my senior recital which just happens to fall one week before this Tohono Chul Concert, and that is 60 minutes in length. I had a head-start. But then again, 20 minutes of extra music (a 90-minute concert with a 10-minute intermission included) is not something easy to just put together for a concert, either.

Aside from the sheer act of figuring out what to play to fill this time, which in hindsight was not the scariest thing, what really took learning to process was the pure stress of it all.

It was easy, or rather, natural to let it take me off the deep end, and I will admit that it did, several times. But I did not come out of this experience without having learned something about handling this kind of stress, the kind of stress that permeates everything you’re doing and thinking, because at the end of the day, this concert wasn’t going away and I’m still graduating… so I better find some way to make this thing work.

Realizing where “you’ve got this”

When something takes you off guard like this kind of change, I found it crucial to remind oneself of what you do well and what you have going for you.

To start, Tohono Chul is my playground. I’ve been organizing concerts there for two years now, and the audience has followed me the entire ride. I have audience members coming up to me at Tucson Guitar Society concerts just to say that they enjoyed Sunday’s concert. At the end of the day, I won’t be falling flat on my face, it’s just not possible – the audience wants me to succeed too much, like any artist, to let me fail.

It’s a similar phenomenon that I mentioned in last week’s blog post about the healing effect that these kinds of concerts have on the performer, because when an audience is rooting for you, they want the best for you and will do their best from their seats to help in achieving that best.

To remind myself that I am safe up there, that I won’t fail, and that the audience is sure to enjoy the performance, is an incredibly reassuring thing and something I had to learn to do consciously.

It’s not an egotistical thing, either, which is itself a different battle to fight, but instead, it’s done to keep our artistic minds healthy and to give our artistic minds the space to be just that: artistic. Using affirming words and statements, remembering how prepared I am, and verbalizing all these things out loud did a tremendous job at helping me erase away that anxious feeling. And as my mom has always told me, use statements that start with “you” rather than “I,” as it has been proven to build up your self confidence stronger. I constantly mutter the words “you’ve got this.”

I would take my mother’s advice if I were you.

Leaning on friends for support

I’m not revolutionary in saying that it’s ok to elan of others for help and perspective, but sometimes it’s the simplest things that fly under our radar.

So, I did it, and I felt loads better afterwards.

I spoke with my great friend who has her own solo classical guitar concert in the series a week after mine, and expressed these exact worries about putting together a program, playing it all, and worrying about falling short in time and in quality of my performance. She had some great perspective about these Tohono Chul concerts that even I overlooked.

Know the nature of your concert

These “al fresco” concerts are quite casual, and different from the competitions that I am familiar with, no one will be watching the clock to make sure it exactly fits the time requirement. For one, these concerts are outside, and if you’re familiar with Tucson, AZ, you know that the outdoors can get quite grueling around that time of the year. Fingers crossed that it won’t be too unbearably hot, but if it is, the audience won’t be picky about the length of the concert, and might even want that few-minute head start to seek the shelter of air conditioning.

And secondly, this audience expects more than the music, they expect an interactive concert, where the performer engages them in the history of these pieces, fun facts, and the stories the performer has with these pieces. This takes some public speaking experience, some coordination with what you want to say, and some extra buffer time in the program, and I’m happy to say that I can handle all that.

Every week I get up on stage and address the audience without an instrument, only my voice, to warm them up to the performance to come, and I will say that speaking to them does not intimidate me. And when it comes to what I talk about, I’ve had some experience recently with that, as well. You can read up on it in my March 19th blog post, but to summarize, I’ve already had to engage with audiences mid performance using interesting factoids, analogies, and my own relationship to the music. Even though it might have been one concert, back then I had a natural inclination for it, and with this Tohono audience, it should be a walk in the park. I’ll still need to organize my thoughts and develop some kind of script, but at least I know where to start.

After I got a hold of this stress, I was now able to think about the fun logistics: promotion for my concert and what I’ll play.

Graphic design

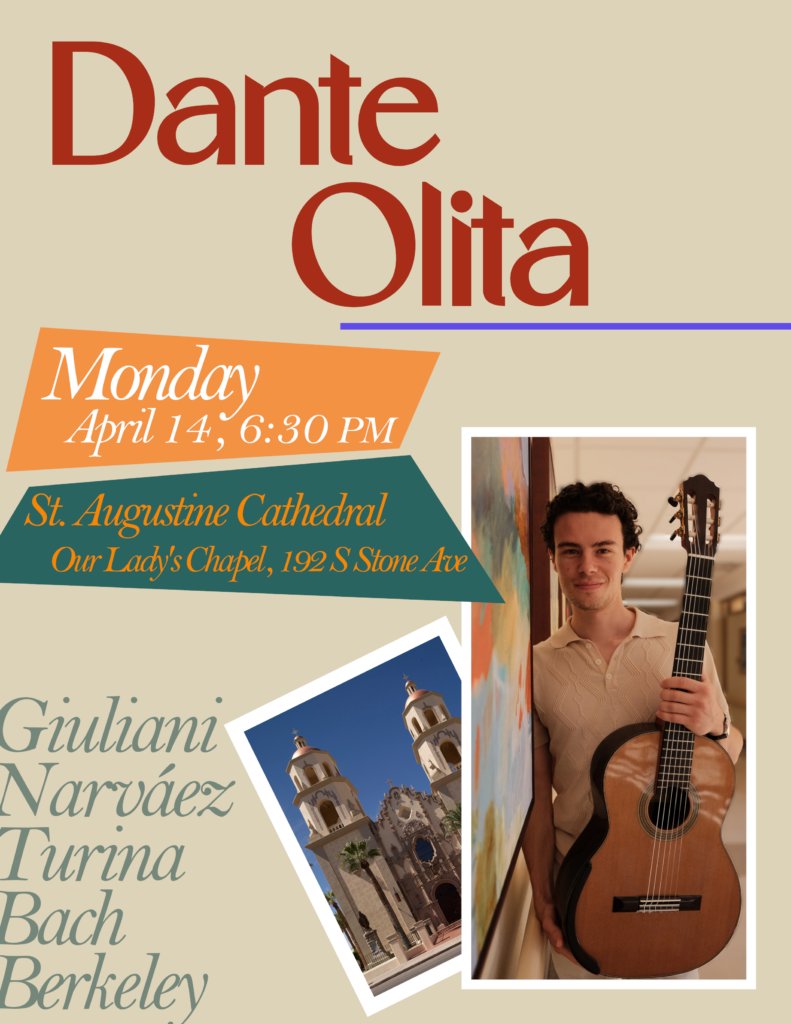

I love graphic design, I’ve been creating posters for musical events for about two years now, and it’s something I look forward to doing, so when it came to getting the chance to create graphics for my own concert, I was excited.

This was not by any means the most difficult graphic I’ve had to design, quite the contrary, as much of the graphic was already created by Tohono Chul themselves, I just needed to add my touch to it, and, you know, my concert details would be nice, too.

This was already a great graphic to start off with, and what I was concerned about was making sure that anything I added would be in keeping with the design philosophy and that would air on the more modern side of things (which is my preference). The placement and size of elements was the most involved part of this, as after I updated the date and chose some colors that would pop and go together with what was there, I had to figure out what would be the best way to highlight myself.

I chose to use photos that have been in circulation on my website, if you haven’t noticed (hopefully you have and have gone head and checked out the rest of my website by now). This was done for two reasons.

- They’re nice pictures! I’m really fortunate that Katie took some of me in the fall of last year that represented the approachable, sophisticated, and fun energy I wanted to convey with my brand. Although I cut out the background, it also helps me knowing that they were taken in from of artwork that is a part of the Healing Art Program, an incredibly formative program in my artistic development.

2. I wanted some consistency across the different promotional materials I would create for the various projects I have going these days, that way there is a common thread of branding. Below, you can see a recital poster I created this week, too, for a different solo concert I have in the works that, as of this week, goes hand in hand with this project (now, I’ll be playing quite a bit of the same music between concerts). psst… please stop by my senior recital if you’re at all interested in hearing my work from the past four years of my college degree!

I won’t bore you with the specific details about what goes into editing a design like this, but I’ll make note that I wanted color to accent my picture, as it’s the colors of the outdoors that are what makes this kind of concert so special and unique.

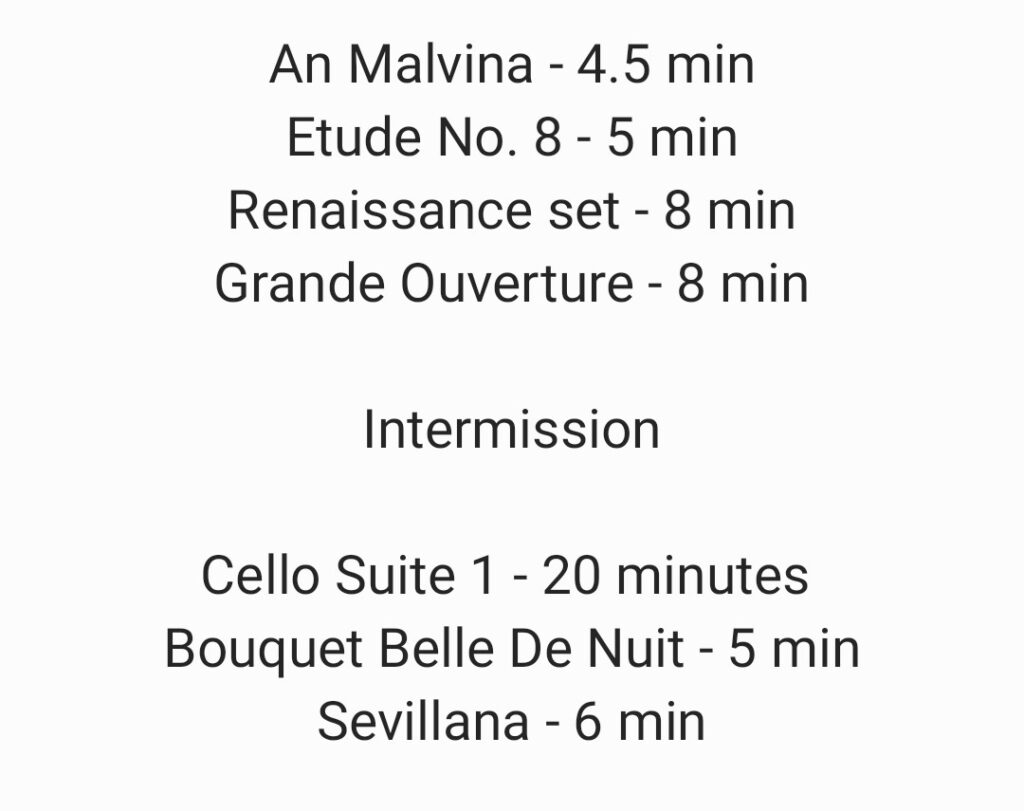

The NEW program

This is what I’ve come up with for my solo concert in the gardens. Trust me when I say this, it’s a bit different from my senior recital program, so you might just have to come see both!

The biggest difference aside from some adding and taking away of pieces (which is linked to this point) is the organization of the program. When I made this program, I had a completely different aesthetic in mind and it completely changed how I approached imagining this concert, which is a great exercise to do if you are a performer. Whereas my senior recital is designed to be more… intense and academic while being artistic and a bit dramatic (it’ll be in a low-lit chapel after all), this concert is naturally different in audience and location, and therefore requires a more friendly, welcoming, and… sweeter format.

You can see this in the order of pieces, for one. I wanted to start with An Malvina by J.K. Mertz because it’s just a great soft opener. A gentle block chord, soothing arpeggios, and a sweet key (G major), all wrapped up in a nice little stand-alone piece. To follow this up, I chose Etude No. 8 by G. Regondi, not just because it’s in the same key and has many of the same characteristics, but also because I frequently play them together at the hospital.

That is the other aspect to how I designed this program – how I can talk about the pieces, when I can talk, and how I can transition between them.

Given that I want to spread the word about music and medicine, it makes complete sense to start with these pieces. The rest of the first half is all about Spain and Italy, and although they are longer, by now the audience should be warmed up to me and ready for something more substantial. And besides, they aren’t incredibly long, at least by classical standards. I thought it would be nice to close the set with something meatier while I still have their energy (they haven’t been outside for too long at this point), that way I can tell more of a story and hopefully entice them to stay for the second half. Plus, I get to talk about my graduation plans of traveling to Italy and Spain, which I’m sure they’ll be delighted to hear!

After the intermission, I’ll welcome them back with the soothing opening of the First Cello Suite by J.S. Bach, and have yet to decide if I’ll talk in between pieces.

Since that is a longer one, I thought I’d break it up a bit with a more folk-esque piece by the great Sergio Assad, Belle De Nuit, the second movement of his Bouquet pour Julia (that is, Julia Pernet, the chairman of the TGS, friend of many of the guests, and who hopefully will be in the audience!). This one has a special connection to me, as I’ll be so excited to thank Julia through music and words for all the help she’s given me with my college career. She’s a gem and it’s the least I could do.

And to wrap it up, the exciting, flamboyant, explosive Sevillana by J. Turina, the true essence of Spain in classical music. With its bombastic ending, it’ll surely get the audience out of their seats. And it isn’t too long, either, which will be nice since it’ll be at peak heat.

Well, what left is there to do than to go and practice. Next time you’ll hear from me I will have given two concerts, had a blast doing it, and will be excited about what the future holds. That is, unless you hear from me from the stage. I hope to see you there!

Reflecting on "Why I'm Doing This"

April 1, 2025

Spending some time for reflection is healthy for anything that we do. Why are we doing it, what purpose do we find in it, what are we trying to accomplish. In a busy world where so many demands are placed on us, there’s not enough time in the day to do it all, and I think a friend of mine just broke the code: she told me the simple act of reflecting on purpose can do wonders.

So here’s my try:

My duo partner, Katie Baird, and I have set out to perform throughout our community in the spaces that need it most, to hopefully help the healing process and to maybe inspire some fellow musicians along the way. Our mission: bring an interactive concert to residents of assisted living/memory-care communities to spread the word about the new directions music is moving and the revolutionary strides it is taking. Surrounding this is the idea of getting music out there, away from the traditional performance spaces you’ve surely seen it in and into an environment that you never thought could have music.

And for our grand goal?

One thing is certain, on April 20th we are scheduled to perform at Tohono Chul Park for an alfresco concert outside in their beautiful performance garden. I’ve always been extremely partial to the work that the Tucson Guitar Society does in collaboration with Tohono Chul to not only bring music to audiences in new and innovative ways, but to give performers a different approach to their artform.

One-and-a-half years ago I shared a concert in this very space, and it was unlike anything I had ever done before. Up until that point, I had been involved with the project in an administrative capacity, organizing the series, bringing artists to the venue, and producing the shows live. It was this chance, however, that I could be on the other side of things as a performer, and if this time will be anything like the last, it will be so refreshing.

As I near the end of my music performance degree (I graduate in May!), I can’t help but reflect on what experiences I had, what I was taught, and how that experience may be unique.

This has been the best four years of my life, and my experience was nothing short of life changing, even if I do see myself going down new and exciting paths away from music, but I won’t stray away from how I think certain aspects of the degree may be restructured to continue to provide value to students and to the real world.

I’m specifically talking about how and where we perform as classically trained musicians, and how a degree in music performance can prepare us to do just that, realistically.

Concert halls are great, but…

I’ve had the wonderful privilege to perform in surely one of the best halls for classical guitar in the world, and I’ve also gotten the incredible privilege to perform music throughout my community in places that are not forgiving to an instrument like the guitar. I won’t get into the specific science behind instruments and how they work, but just to make it clear, the intimate sounding guitar really does need some help when it comes to projection and sound quality. Without those nice, sonorously reflective walls of a concert hall, the guitar might not even be heard, let alone have the wonderful tone that the best concert artists are known for. But I challenge all classically trained musicians aspiring to be one of those concert artists:

Does that all really matter?

I’ll get into why it doesn’t need to from an audience’s perspective, but first I’d like to talk about it from the performer’s perspective.

Healing the performer

Concert musicians, what else is notoriously associated with these gorgeous concert halls? Our compatriot, performance anxiety.

Now, we all have our own relationship with performance anxiety, and it undoubtedly comes from within us, but there is no question that external environments provoke it, and, contrastingly, help it too.

How do you think it feels when you perform, probably a mistake here or there, and you look up and see happy, loving faces and warm applause.

No dark abyss of bodiless sounds from a distant, twice removed sense of praise. Pure positive feedback. If you think it feels wonderful, empowering, and fun, you would be correct. Take it from me, someone who has performed more than 100 hours in these non-traditional performance spaces.

I feel this point is rarely talked about, or if it is, not artfully, especially when we talk about community outreach. The cognitive dissonance is real when you talk about how an action dedicated to helping others fills your cup at the same time, but I don’t think there has to be an egotistical side to it. We musicians are humans too (I know, how astute), and it’s important that we make a pursuit as stressful as this sustainable for ourselves, so that we can continue to perform, including for the community.

This renewed sense of appreciation permeates everything we do with our music because it builds up our confidence, and at the end of the day, reminds us as to why we should do it: to improve life around us. The audience enters into an interesting relationship with the performer when they listen to a performance, and although we may think they’re out to pick at our mistakes, in reality they just want to see us do well.

I have the privilege of being at Tohono Chul every Sunday in the months of April and May, and even when I’m not the ones on stage performing, it is so heartwarming to see how music can move audiences, and how a space like the garden can make a world of difference in how that message is received.

Just this past week the wonderful Las Azaleas performed mariachi-inspired folk music from prominent Latin American women composers, and the way the audience lit up, swayed to the music, and even started dancing was humbling. There’s something special about that space.

Demand change from higher ups

But this idea, understandably, is a bit foreign to us, and I feel in large part because it is not communicated frequently enough that it can be “The Goal.” Motivate your students to get out and play for anyone and everyone, everywhere. Those higher up are the examples, and it starts with them to set some kind of example that playing in these spaces is acceptable and desirable. Heck, even make it a part of the degree requirement! This is probably easier said than done, but I think as a collective unit it is possible.

Be daring, be creative

And we don’t have to wait for the admins to do it, we students can make the movement happen. Get creative, let your imagination run wild, there’s no limit for where you can perform. Schedule concerts on your own in these spaces, reach out to people and surprise them with your ideas, and try to even use these concerts as degree requirements.

(Ok, so this last one is pretty tricky, since I did try it myself, only to be met with resistance from my professor. But that didn’t stop me, and even though I’ve been encouraged to hold my senior recital in a different location that’s more “appropriate,” I kept that April 20th Tohono Chul date on the calendar and I’m excited to give a great performance.)

Support your colleagues!

These changes in the status quo do not thrive with only one person, it is all of our artistic responsibilities to support the change we want to see. There are more of us out there, some of the most talented of us all, too, doing these very things we may think were impossible or subsidiary to the concert hall.

On Thursday, March 24, I went to TMC’s Rich with Life Park, a newly-constructed outdoor amphitheater dedicated to bringing music to the Hospital Community. There I saw my great friends and colleagues, all phenomenal musicians in their own right, perform a benefit concert that raised unrestricted funds for hospital operations. Great music, great food (yes, they even had food), and a great time; what more could you want.

With all of these phenomenal examples all around me representing what I know music is meant for, I can’t help but do my part to help pave the way. So I will!

April 20th, I’ve got my eyes on you.

Administration Behind the Scenes

March 19, 2025

Let’s face it, a concert can’t happen without the behind-the-scenes administrative work that pulls the strings and truly coordinates all the moving parts. Neither Katie nor I are unfamiliar with this process, it’s actually quite the contrary, Katie (and virtually myself) work this job professionally. I organize the bi-annual Sundays in the Garden concert series at Tohono Chul Park and Katie manages events at Tucson Medical Center, most recently the Healing Harmony Concert Series. We know how to approach this, so this week’s tasks are a bit easier to manage.

As soon as Katie and I met, we had had thoughts in the works about one day performing together, and one year later we find ourselves embarking on a concert-series journey, hopefully organizing concerts for residents of assisted-living and memory-care centers (I say hopefully, because as with most professional opportunities, you don’t always get a call back).

Since we began thinking about this idea, we immediately started thinking about what repertoire we would choose, and in recent weeks we went through that process of making an ambitious dream a manageable reality, finalizing our program to a format we are happy with (check out the previous post on this page for that program).

This week it was time to begin our pursuit of securing the other aspect of a concert, location.

The Cold Call

After doing a bit of research about our community, spreading the word about our project, and following up on leads given to us by friends and colleagues, we finally created an organized idea of what we’re looking at. Where could we play, how do we get in contact with them, and finally what our pitch will be.

Of course, we’re still scheduled to perform at Tohono Chul Park as a part of the Sundays in the Garden Concert Series that I help organize, so we have one guaranteed concert, which is already a win! Having this location secured already has really allowed us to set a tangible goal of when and where we see ourselves performing, which not only does a great deal for our confidence in our ability to execute this project to some degree, but also in making our practicing goal oriented.

But what about our mission to perform out in our community for the purpose of healing?

From Katie’s background in pursuing this very thing years ago, it’s not easy, and at the end of the day, dictated by the interest and availability of the facilities we want to go to.

First things first, where do we want to play?

I’m really grateful for Katie’s background in this kind of work because it has helped encourage me in my own pursuits with this field, as well as given us a starting point for our project.

Naturally, Katie has remembered a few locations from her time performing out in the community that really loved her music, so we though to start there.

Using proven past experiences is a great place to start with this, as it helps tackle that question-mark element of whether a location will be interested. If we can make our efforts targeted towards a place we know has had live music in the past, and that they enjoyed it, it’s more likely they’ll say yes this time around.

And I just had my own experience with this, too: I performed my first solo concert for residents of an assisted-living community!

The best thing about these concerts and the natural format they assume (direct interaction with residents during and after the concert), as it gives you so much valuable information about performing for these audiences again.

To start, once you finish your performance, there’s no running off stage, no hanging out in the green room, and no disappearing out of the back door. When you finish performing, there’s no where else to go than straight to the eager questions and joyous smiles from the residents.

As soon as I played the final note of my set, I was sharing with them my plans for the future and when I would be back (because they were very vocal about hoping that I would). This kind of immediate post-concert interaction is quite humbling and healing for a performer, which was a welcomed added bonus.

I had driven up to this concert nervous that I hadn’t warmed up enough, that I’d be unprepared, and that therefore I’d reenforce bad habits in my playing (I was performing pieces from my upcoming senior recital, so this last one freaked me out even more).

But then I played, mistakes and all (I’ll admit it wasn’t perfect), and immediately I saw what kind of impact those 45 minutes of music had on their spirits. They seemed so grateful to have been given a chance to escape in their imaginations, in their memories, and in the music, and I could never have expected how beautiful that would look like. I was very lucky to have gotten the chance to see all that the moment I looked up from my instrument. How’s that for healthy reinforcement as I’m preparing for my recital.

What’s more, I learned a lot about how these concerts work. Frequent interaction with audiences in between pieces and even in between movements; telling short and engaging stories about the pieces I performed; trying to inspire audience engagement by asking them questions about their lives to help them approach this foreign music, all of these can be seen as crucial elements of a successful community-outreach concert. Katie came with me to this and was able to tell me all the things I did well when it came to providing these services.

And for constructive feedback, all she had to say was how I handled the post-concert meet and greet. I’m so used to audiences stampeding out the hall when a concert is finished, but these people were happy to sit there and wait a little longer, maybe even hoping I’d perform more. This surprised me and, admittedly, I had no idea how to proceed. So, I sat there, waiting for them to either ask me questions or leave. I learned from Katie after that that didn’t quite help in communicating clarity that the concert was, in fact, over. Good to know for the next one!

Organizing your thoughts

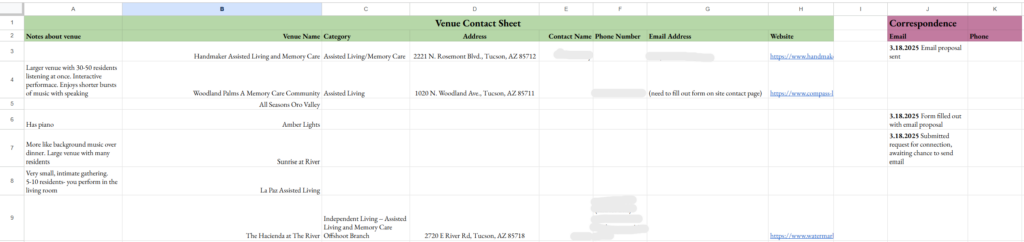

Great experiences, a great track record, now for a great database of info.

When you’re eager to get out there, you have to be economical about how you use your energy.

We opened up Google Sheets, formatted a table, and got to unloading all that info.

To be economical, we wanted to be as clear as possible with formatting, that way we wouldn’t have to look at different places for the same type of info. This formatting process is harder than you would think, and after stumbling through a bit, I think I can reflect on what works and what doesn’t in this process.

Brainstorm, even when it’s about an organizational tool

Get out a scratch sheet of paper and write. Write what info you do have, write the labels you want to use, and draw connecting lines between all of these things.

I our case, we did this out loud with one another, but the process was the same, and if you saw our document history you would see how many edits we went through to get that final image.

Have fun with the small insignificant details

I like design and a good looking final product, so we had some fun figuring out the colors of everything and what would be colored at all. Choose your favorite font, too. Experiment with it all. It may sound silly, but finding a way to make it interesting, satisfying, and engaging is a great way to inspire a good habit of this kind of organization, especially when we’re dealing with such dense material like this.

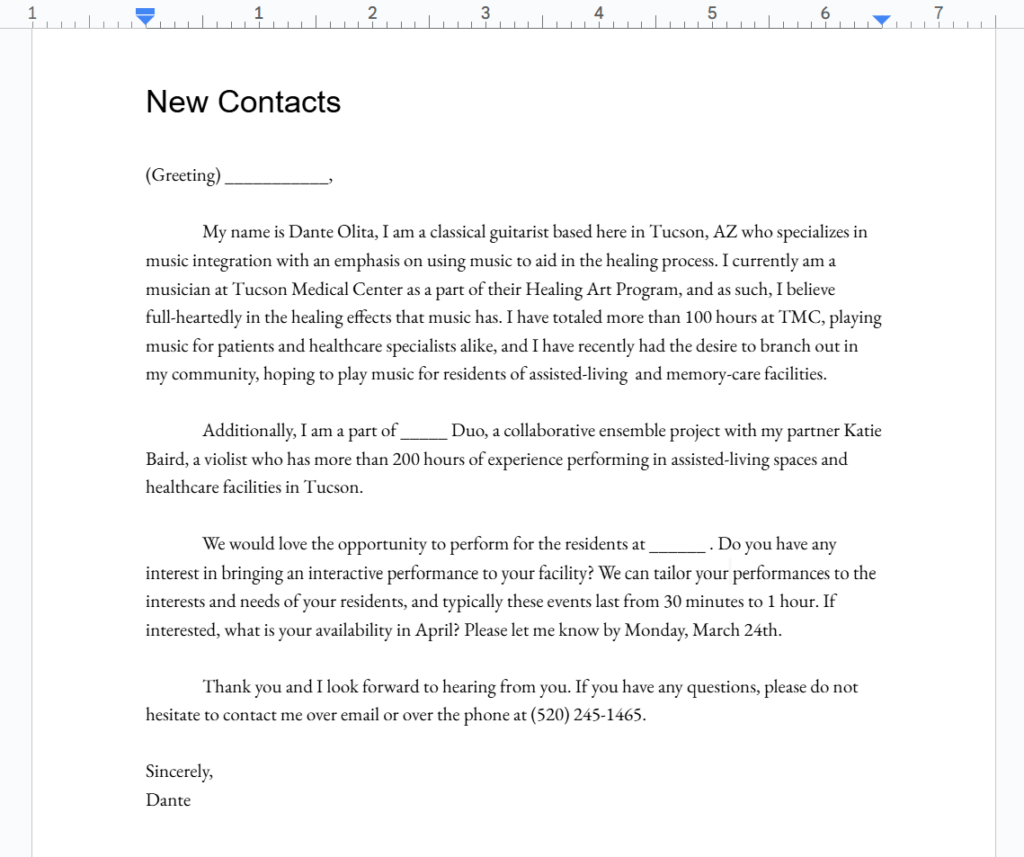

The elevator pitch

And finally, time for what we’ll actually say to these folks to get them to invite us to play. To preface this, I’m no expert in this and after looking at what we sent out, I can already see improvements that we can make.

The bottom line is that we need to sell ourselves by establishing trust and authority and we need to communicate how we can provide a service of value to the residents and facilities. We need to be clear and concise, too, and not sound like spam!

This isn’t explaining how great we as musicians are, this isn’t an ego trip; this is about how we can convince them that their needs are met by our service, which objective, they are. It is to this point that I would like to critique our own pitch.

The final paragraph serves this function very clearly, only I think we could expand a bit more on how this service, and in turn this value, is something that they may not have thought that they needed. As I’m looking back at this, it could be nice to include a sentence or two about the fact that music is scientifically proven to help people in any form of compromised physical state, whether that be in the hospital or in an assisted living facility. The only challenge I can see to this is making sure, again, that it does not sound like spam, and to use this information in two effective ways: one, identify a problem that the facility would like to help solve (the health and morale of their residents), and two, further develop trust by using credible sources.

I’ll have to keep you all updated in the coming weeks on how we revise this moving forward, and hopefully on whether or not we get any responses!

Creating the Perfect (for now) Program

March 18, 2025

If you haven’t been keeping up with the past few posts, I’ve embarked on a kind of concert series debut with my duo partner Katie Baird, violist and music integration specialist. As the weeks progress, our ideas for the scope of our plan change ever so slightly, but one thing is clear: that by the end of this, by April 20th, we’ll have performed music for residents of assisted living facilities on our journey to making our public duo debut at Tohono Chul Park (join us that Sunday morning if you can!).

With this project, a name for our duo and series coming down the line very soon, we want to highlight the healing impact that music has, and in the process, highlight a unique instrument pairing.

Katie and I have both performed more than 300 hundred hours collectively for patients of TMC hospital and for residents of assisted-living and memory-care homes across Tucson. The inspiration for this project came from our shared background in this emerging sector of the arts, as well as from our discovery of contemporary pieces written for the viola and guitar.

We’re still in the (somewhat) introductory stages of this project, and I will be the first to admit, planning a project like this with your partner can be really exciting, and be aware one may let their imagination run wild… sometimes, a little too wild.

We were a bit ambitious.

Five or so new-to-us works, all to be perfected, performed, and for some, even transcribed by the beginning of April, all the while Katie and I juggle our busy work and school lives. I have a senior recital in the works, culminating in a concert one week before (please come to this as well, if you can!), Katie a concert series she organized for TMC (go to that, too!), and on top of all of this, our aspirations of creating a full-fledged professional duo.

Good luck.

So, the question arises: how do you change a plan as involved as this?

Learning to accept change.

It’s ok to change your plans, and it doesn’t have to be scary.

I will say, it scared me to have to say out loud that I thought this may be too much all at once. There was something about it, the feeling of doing something wrong, breaking the rules, letting myself down, or some emotion found in between these things. And I don’t think this is a unique experience, either.

Katie felt the same way, and if you’ve been raised in the high-stakes classical-music mindset of today, or even just find yourself as a creative person in our society, I’m sure you’ve felt the same way, too.

But then I did something courageous: I said it all out loud.

And what happened? Katie followed close behind, and magically, we were on the same page, which was great because it’s a duo project after all.

It’s better to be honest with ourselves and our honest assessment of our capabilities than lead on some dream just to be stressed when it comes time to execute something we’re not ready for.

So, with that out of the way, it was time to figure out what would change.

Making a program.

Obviously, it’s one of the most important steps to putting on a concert, knowing exactly what you’re going to play, how long the runtime will be, and if you want to do something special, knowing how to pair certain pieces to create a logical and engaging listening experience. It’s more involved than you would think.

Predominantly, what we first thought about was difficulty, given all of that life stuff going on that I mentioned earlier, and this is where we had to send some pieces to the chopping block.

We had a piece by Carlos Fariñas in mind that we received from an acquaintance of ours who had worked in a guitar and viola duo before and who transcribed these pieces for the duo, Joaquín Clerch. Now, as much as we fell in love with this piece and would very much love to give it a go with our duo, April just may be too soon on the horizon to get it to the level that we want. We’re not saying no, and there’s always room for another few-minute piece, but for now, we’re focusing our efforts somewhere else.

And from my perspective, I hoped to have transcribed a few pieces myself to debut with this project, Carlos Gardel’s Por Una Cabeza and Sergio Assad’s Menino. For the Gardel, I have the chord progression down, which is essential to this kind of music to support the melodic line that Katie would take, I just have to develop a strumming technique that is authentically tango. Luckily, there are specialists in town that could help me, but I’m not too sure I could figure that all out by April at this point. A crowd favorite, but it probably should be put on the back burner. And for the Assad, that one is a bigger undertaking. Last Summer Sergio Assad himself sent the music to me, I’ve worked with him in masterclasses several times and was excited to share my aspirations for playing his music in a duo with Katie, only the guitar sheet music for this one piece wasn’t with what he sent me. I figured he was just that great of a guitarist to be able to play his music without writing it down, especially with a sweet folk-esc song that this piece is, so I was left to transcribe by ear and from the short video clip I have of him playing it. Needless to say this will be a dream piece that we’ll work on after this project is wrapped up.

But we’ll have another great program to play with all of these dream pieces, I’m sure!

So now for what we’ll play.

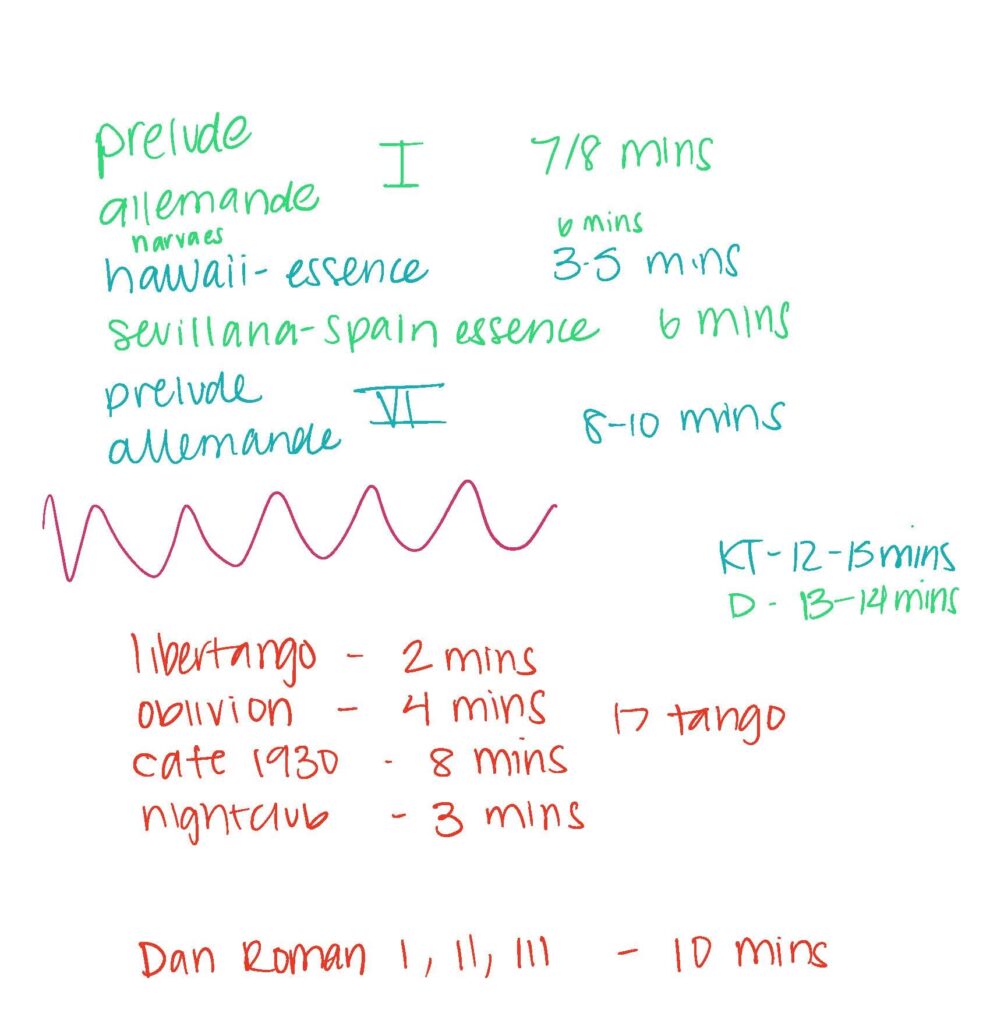

Katie and I performed a concert like this last year for folks of an assisted living community, and we made a small program that we felt really worked. We’re shooting for around 60 minutes worth of music to Meet Tohono’s requirement, but we’ll cut this down to around 45 for the community concerts. When we performed last year, we paired some solo music introductions with our duo music.

We’ll start with a solo-performance exchange. Some pieces from me, some pieces from her, some pieces from me, some pieces from her.

I’ll start the set with the Prelude and Allemande from J.S. Bach’s BWV 1007, the First Cello Suite. We chose this because it’s a nice welcoming piece to warm up our listeners to myself, our duo, and just a musical performance in general. Check out my interpretation of it below! And after that, I’ll introduce some early Spanish music by Luys Narváez to contrast time periods of a united culture later on in the program.

Next, Katie takes the stage to perform some “cultural” music, a piece by Hawaiian composer Leilehua Lanzilotti called Ko’u Inoa.

We want this concert to have a common thread in which most of the music is linked, and we felt the best link would be music that represents the cultures of nations around the world, hence Katie’s showcase of this beautiful contemporary piece that reflects on the ambiance, emotions, and essence that the composer felt represented Hawaii.

I’ll come back once she finishes with Sevillana by Joaquín Turina, a classical composer from Spain whose work was heavily, heavily influenced by folk music of the region, especially the art of Flamenco. Flamenco is so deeply rooted in Spanish artistic culture, so we felt this would be a great touch to the program, and a great contrast to the introspective Hawaiian piece that came before it (if you couldn’t guess, it’s loud and exciting).

To close off the first half, Katie will perform the Prelude and Allemand from the Sixth Cello Suite by Bach, to not only provide two bookends of the first half of our program, but to also serve as a talking point about how music, especially from one composer, may evolve over time while maintaining its characteristic qualities that defines the work of that composer.

Once our audience has gotten warmed up to us as individual performers, now they’ll get to see us as a unit. After the intermission comes our duo, works predominated by Latin and Central America.

We’ll start with the Tango of Argentina, featuring works from master composer Astor Piazzolla. Libertango, Oblivion, and Histoire du Tango’s Café 1930 and Nightclub 1960. Although these pieces have been performed countless times by duos, we think our viola-guitar pairing will provide a nice breath of fresh air into the mix.

And finally, the piece we’re most excited for, El Grand Mambo by Dan Roman, written specifically for viola and guitar and a rare gem of music. If you go looking for this piece, you’ll have a hard time finding it because it’s only been recorded once by the duo it was written for. We seek to change this. From Puerto Rican composer who chose to write a Cuban Mambo, this piece is a great interpretation of folk music form a minimalist classical perspective. The piece that really inspired our duo, we’re so excited to finally play the entire three-movement work for the public.

Well, thanks for stopping by and checking in on our project. We’re off to start practicing now, so tune in in the coming weeks as we develop our promotional materials, reach out to interested venues, and finally perform!

From the Concert Hall to Out in the Community

February 25, 2025

I love non-traditional performance spaces. My duo partner, Katie Baird, loves them. But sometimes, learning how to perform in them means performing in the concert hall first. Katie and I specialize in these types of performances, bringing music to places where it wasn’t previously deemed possible or welcomed. Need only look to our collective 200+ hours of performing music for patients and medical professionals at our local hospital to see that we really are passionate about this sort of thing. And I find myself at this time of year again, where my role as Director of the Sundays in the Garden concert series comes into full swing, successfully (hopefully) producing eight concerts at the outdoor performance garden at Tohono Chul Park in months of March through April.

Katie and I had the brilliant idea of melding these passions of ours, and have began to embark on a concert series of our own, one where we will perform music for patients of assisted living facilities and memory-care homes. Across Tucson, Ariona, we will visit residents of these facilities and curate a concert for them, performing little-known works written and well-known transcriptions for viola and guitar ensemble.

Where last week we dug deep into what it meant to interpret a piece of music from a foreign culture, this week our undertaking was actually performing and the rollercoaster of emotions and experiences that come with the territory.

Performing for a crowd is not easy.

Really anything can happen on stage and its really difficult to prepare for every possible scenario. You can do hours of practice even more hours of memorization and visualization but it always seems like there’s something that will catch you off guard.

As musicians, especially as musicians built on the idea of being perfectionist, its an interesting thing showing a mistake. Much of our training as classical musicians tries to prepare us to eliminate mistakes in every possible way. This culminates when we find ourselves in front of a crowd.

So when you make a mistake in front of a crowd, our training kicks in and we have to do everything we can to not show that mistake, and mentally we cant do anything but focus on the fact that we made a mistake. We have this weird paradox where we want to hide our mistake but hiding it from ourselves is the last thing we can possible do. Overcoming this, especially in the span of 20 seconds, is probably one of the hardest things we can do as performers, and one of the most fascinating things that we can come to terms with. This happened this very night when we performed to my partner Katie.

My partner made a mistake. But can you even tell? No, but Katie definitely did and I could immediately pick up backstage the familiar wave of anxiety that our hard work didn’t go according to plan.

Why fear the mistake?

So what was it about this mistake that was such a big deal anyway? We kept our cool on stage and yet still, that cold feeling crept up on her afterwards. What I think its come down to is expectations, the ones that we have for ourselves and the ones we think that people have for us. Tis was no ordinary Saturday night concert, this was a concert (that I let Katie know about the night before) for THE David Russell, one of the most distinguished and incredible classical guitarists alive. That’s no small crowd. And here we are on Holsclaw Hall stage with one shot to play for this giant and we obviously wanted to make it good. This expectation of what somebody of his caliber would demand from a performance influenced our own expectations of ourselves. We didn’t hear anybody say we have to play perfect, we didn’t hear anybody say he was looking to find mistakes (which he is far from that), we just told ourselves that that was expected. That’s a lot of pressure for a five minute performance.

What actually happened

I couldn’t tell you, really. Half a measure off at one point, and a couple missed notes gave us the impression that the whole section, and therefore the whole performance fell short. I spoke with Katie afterwards and she shed some light as to what she was going through.

“I flipped the page one too many times and couldn’t find my way back in the sheet music. I didn’t quite trust my gut… And I just forgot what came next.”

To use or not to use sheet music in a performance.

It’s always a tricky situation when a piece is somewhat new and you think sheet music could help you, but maybe you can get through it in one go without looking. I don’t know the science behind it, although I’d like to do some research on it, but I’m sure this happens from our brain’s inability to multitask.

How is reading and playing the same music multitasking, you might ask?

Well, they are completely different things, in reality. On the one hand, one action uses your memory and sensory self-monitoring of your playing to move you along; playing a piece by memory. You trust your muscle memory, you hear yourself, and you just know what comes next. The other action involves interpreting your vision, anticipating what you will see, and converting that into muscular movements. When we play and read at the same time, we’re not really hearing ourselves, but really relying heavily on our eyesight to give us the answers.

What comes from this is our body and mind at odds with ourselves.

This leaves us with one choice: to make a choice and to stick to it. Go for it.

Of course, you have to feel comfortable with playing by memory a bit before you do, but at some point, you have to just trust in yourself. Know that you know where to go, what comes next, and that, in special cases, your partner’s got you.

And we can develop this trust in ourselves.

There’s surely countless exercises that you can train your memory of a piece, from visualization of the sheet music and of your performance, thinking of every note, to memory drilling like I’d like mention here.

This works best with a partner (but even I sometimes have to do it alone when Katie’s called it a night), but how it works is: your “partner” follows along your playing with the score, and at random, incredibly inconvenient times, they tell you to stop playing. But don’t take this as the chance to go on a mental vacation. They’re still following along, and when they say go, you better pick up and play where they are.

It’s really difficult, but sooo helpful.

If you want to try it for yourself, I’ve included an audio snippet I use in my own practice:

Losing the Pressure

Remember that pressure we “felt” from the kindest, sweetest, most approachable guitar icon? Well, we have to attack that too if we’re going to have fun up there, both on stage an off.

1. Let it all go

I love to do meditations before going on stage, visualizing why and who I’m playing for, how prepared I am, and how much fun it is to perform in the first place. Walking on that stage should feel like a treat, not a chore. Take a minute, maybe five, before you walk into the backstage, or even when you’re already there, and just breathe, thinking of a “happy place.”

2. Getting Thicker Skin

We’re all going to mess up. It’s natural. So why fight it? Why beat up on ourselves for something the audience couldn’t even see?! Then don’t. I’d love to say more about this, but its as simple as that. And it’s ok to forget that sometimes, I know Katie did backstage. I was happy to remind her of the fun we actually had at the expense of “perfection.” Our artistic worth does not rely on perfection. Our artistic worth relies on our art.

3. Play Outside of the Pressure Cooker

If you’ve ever been to Holsclaw Hall you know its stressful. For any concert hall for that matter. I still get stressed, and I’ve had the chance to perform there for four years. This is where part of my inspiration for my modern work with music came from.

Play somewhere with NO pressure. Find a place for you where you can get out there, playing for people, and developing good, healthy experiences doing so. While you’re at it, play for the benefit of the community, and you’ll discover real quick how it humbles you, changes your entire approach to this craft, and does so all for the better.

Keep following this little series to see what potential this community work has to offer.

A Duo Project to Bring The World to Tucson

February 18, 2025

Imagine: the eclectic music of Central and South America played in the halls of assisted living communities throughout Tucson, Arizona.

When I brainstormed last winter with my partner, Katie Baird, about a potential project I would undertake in my senior year of my bachelor’s degree, it was a no-brainer that we had to create a duo project aimed at using music for healing as a wrap up to my college experience. Allow me to introduce ourselves: I’m Dante, classical guitarist and Healing Arts Musician at Tucson Medical Center; and my partner is crime is Katie, violist, Healing art Musician, and TMC’s Special Events Coordinator. Since our start at TMC two years ago, we have collectively performed more than 200 hours for patients and medical professionals throughout the halls of our community hospital.

If you haven’t picked up on it already, we are both extremely passionate about the future of music integration in the healthcare industry, and how we see it, the future is now. What better opportunity, then, than this one to create something for this mission. And so, we have decided to create a viola and guitar music-integration duo, and uncommon pairing, performing the music of Central and South America in our very own concert series, aimed at providing music for patients and residents of assisted living facilities across Tucson, AZ.

Why do I say that this is an unusual pairing? Well, you would be hard pressed to find many chamber music pieces written for the viola and classical guitar, let alone ensembles transcribing and performing music for this partnership. The closest “recognizable” piece you’ll find to this pursuit is the Arpeggione Sonata by Franz Schubert, a sonata written for piano and the guitar-viola-combination instrument known as the arpeggione, and even still one of us would have to transcribe something (and just wait, the Arpeggione Sonata is on the horizon for us, eventually).

We knew, then, that we would have to look deeper. And look we did, only it seemed that the searching had already been done for us years prior by Katie herself. In Katie’s college career she was integrally responsible for the International Viola Society’s database on BIPOC and underrepresented composers, in which she and her team collected pieces from more than 1000 composers globally. Among that bunch, to our excitement, we found several generally undiscovered pieces written specifically for viola and guitar. And here we find the Latin American “link.”

There is no removing the nylon string guitar from the musical culture of Latin America. As I had known since the start of my upbringing in the craft of the classical guitar, Central and South America are home to some of the most important composers for my instrument. Villa-Lobos, Antonio Lauro, Agustín Barrios Mangore, Leo Brower, and Sergio Assad to name a few are from the countries of Brazil, Venezuela, Paraguay, and Cuba; and what makes them so special is the permeating influence that the music of their cultures has had on their compositions. I bring this up to reference how crucial the musical art forms from these nations and cultures are to the guitar, and by extension, how important they are to a viola and guitar duo such as us.

What immediately stood out to us in this database was a piece written about one of these very cultures from a composer born in yet another one of these cultures: El Gran Mambo by Dan Roman; a puertorriqueña composition written in the style of a Cuban Mambo. The catalyst for the creation of our concert program.

We took to brainstorming, listening to some of our favorite Latin American musicians and composers and devised a complete program of the music from these cultures, including Tango works by Astor Piazzolla and Carlos Gardel, The Cuban Mambo by Dan Roman, and a piece by Brazilian Composer Sergio Assad.

And now the difficult part – realizing these pieces in our duo.

When we started this process this week, we quickly realized how important, and at times difficult, it is to highlight the undying, continuous heartbeat that is the rhythmic pulse of this music.

This process comes in two stages: 1) understanding the conventions, and 2) working on their implementation.

Understanding the Conventions

Listen, listen, listen. A composer can write down accents and rhythmic figures, but it is only after listening to the music of the region that you begin to feel the beat. We decided to start looking at the music of the Mambo to help us better understand our latest undertaking that is El Gran Mambo. We are by no means experts at this point, far from it, but I think after this week we are one step further in the right direction. Tito Puente, Celia Cruz, and Chucho Valdes made up the soundtrack of our lives this past week, and for good reason. Some of the most important figures in Cuban music, these artists exemplify the best of the best, innovation, and experimentation, and interestingly enough, with that same unwavering Mambo rhythm underlying it all.

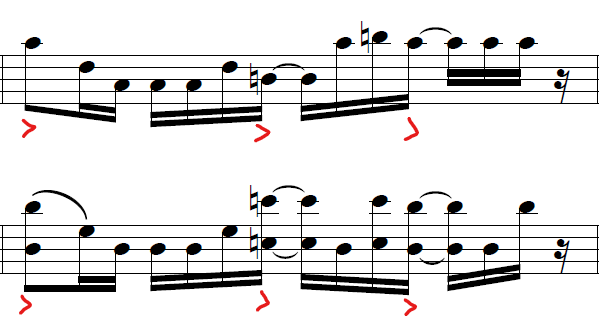

Although there are countless rhythmic patterns and clichés that can be found as the foundation to a Mambo, the one that works as the framework of our piece appears to be quite straight forward.

Above is an excerpt from one of the first few measures from the third movement of El Gran Mambo. I have gone ahead and written in the accents that are crucial to feeling the swing of this piece and rhythmic cliché, and of note that the composer did not write in himself.

Pay close attention to those final two accents on the off beats, as those are the special touch that gives this music its swing.

Speaking of accents, when talking about any ensemble performing music of any variety, coordination among the instruments is crucial, and in regard to this specific repertoire, is key to making it or breaking it.

Implementation

Just yesterday I had the privilege to attend a masterclass on a Brazilian piece of music written for cello and guitar (by Sergio Assad) taught by one of the best classical guitarists of our time, David Russell. In this class, he explained this very accent-coordination.

I’ll do my best to summarize:

Although both string instruments, the guitar and viola, or any bowed instrument, work in substantially different ways. Note decay. When talking about note decay, we are referencing the sonorous transformations that a note goes through after it is played. On the guitar, as soon as the note is plucked, the sound will continue to, and quickly, die away. On a bowed instrument, however, the note being played can grow louder after its onset.